The attention received by Hobby Lobby, the Green Family, and their Museum of the Bible from a New York Times article in early April warrants an overview of the company’s inadequate legal compliance efforts when acquiring and importing certain cultural property, as well as a few brief notes on the cautions and obligations of acquirers and importers of cultural property.

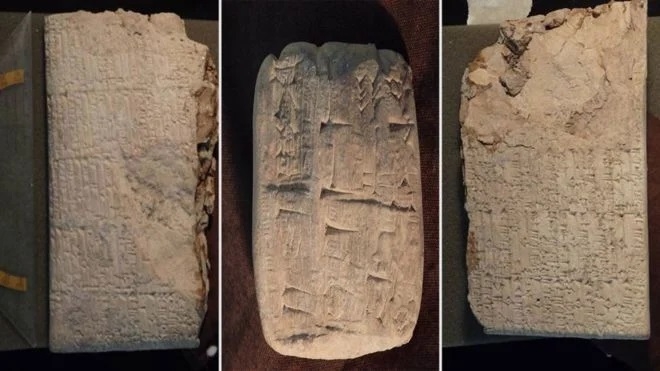

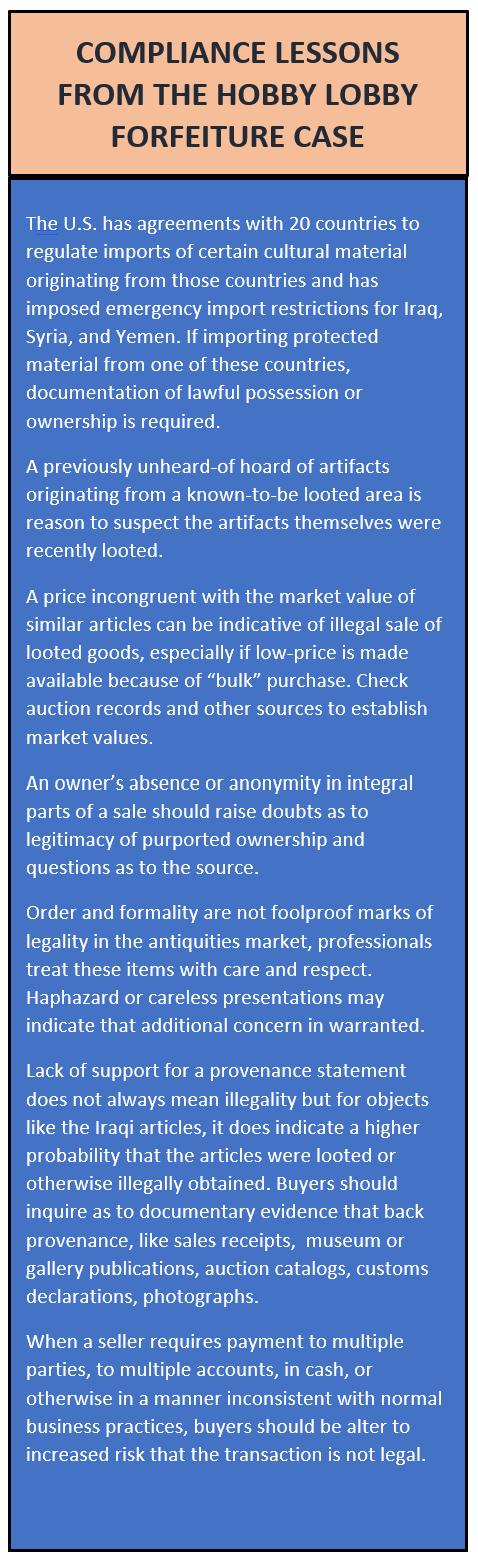

In July 2010, Steve Green, president of Hobby Lobby and co-founder of the Museum of the Bible, visited the United Arab Emirates with a consultant to inspect a large cache of Iraqi artifacts comprised of cuneiform tablets and bricks, clay bullae and cylinder seals. After the visit to the UAE, the company solicited an expert in cultural property law to present particular issues pertaining to cultural property acquisitions and imports. The company did not reveal to the expert any specifics about the pending acquisition though the expert’s memorandum did detail the sizable risk in acquiring and importing Iraqi cultural material. Nevertheless, in December 2010, Hobby Lobby entered into a purchase agreement for 5,500 of the Iraqi artifacts at a price of $1.6 million.

The details of the acquisition should have raised concerns. Present at the July 2010 inspection were two Israeli antiquities dealers and one dealer from the UAE. The purported owner of the artifacts was not present at the inspection. There was confusion amongst the dealers over the storage location of the artifacts prior to their inspection. Further, the articles were informally and haphazardly presented at inspection. The dealers later provided a scant provenance statement for the articles, which indicated only that the articles were legally acquired in the 1960s from “local markets.” At no point did Green have contact or communications with the purported owner of the articles. Especially suspicious was the fact that Hobby Lobby was directed to issue payment for the articles to seven personal bank accounts, none of which were in the name of the purported owner.

The shipment of the articles was equally dubious. In the first round of shipments, the UAE dealer sent seven packages to three different Hobby Lobby addresses. The packages were identified on the shipping label as “ceramic tiles or “clay tiles (sample)”. None of those shipments were formally entered, as required by U.S. law (19 C.F.R. § 143.21(a)). A second round of shipments consisted of eight packages, five of which were intercepted by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (“CBP”). The shipments were accompanied by false invoices and false shipping declarations, purposefully misidentifying Turkey as the country of origin and grossly undervaluing the articles.

In January 2011, CBP seized the five detained packages and eventually instituted forfeiture proceedings for the artifacts under the authority of 19 U.S.C. § 1595a(c)(1)(A), 18 U.S.C. § 542 and/or § 545.

19 U.S.C. § 1595a(c)(1)(A) provides for the forfeiture of merchandise that is introduced or attempted to be introduced into the United States contrary to law if that merchandise was stolen, smuggled, or clandestinely imported or introduced. 18 U.S.C. § 542 prohibits the entry of merchandise into the U.S. by means of false statements and 18 U.S.C. § 545 is a general prohibition against smuggling merchandise into the United States.

19 U.S.C. § 1595a(c)(1)(A) is read and interpreted as having two distinct elements. First, the importation or introduction of the property must have been “contrary to law.” Second, the property must have been “stolen, smuggled or clandestinely imported or introduced.” To satisfy the first element, , the government sought to show that Hobby Lobby imported the Iraqi articles “contrary to law” by citing to 18 U.S.C. § 542, which prohibits an importer from providing false information on customs forms or other entry documents. Regarding the second element, it has been held that intentional and materially false statements in violation of § 542 also satisfy 19 U.S.C. § 1595a(c)’s requirement that the property be “stolen, smuggled or clandestinely imported or introduced.” The government also cited to 18 U.S.C. § 545, which forbids purposefully evading the import process by false or fraudulent declarations (e.g., declaring the value of a package to be $280.40 when it is actually valued upwards of $16,000 to make it seem as though no formal entry of the package is required.)

The government bolstered their characterization of the Iraqi articles as “stolen, smuggled or clandestinely imported,” by citing several provisions of Iraqi law. First, the government cited an Iraqi “patrimony law,” which places ownership of all antiquities found in Iraq after 1936 in the national government. Antiquities under the purview of a patrimony law that are moved or transferred absent permission or some other grant of authority are thus stolen property. A separate provision of Iraqi law generally prohibits the private possession of antiquities but where private possession is allowed, the antiquities must be registered with the Iraqi government and any transfer of the antiquity must be approved. Presumably, articles subject to these protections and transferred pursuant to the mandated processes (i.e. legally) would be accompanied by validating, authentic documentation or would at least be on record with the Iraqi government.

To further demonstrate the illegal nature of the articles and their importation, the government relied on U.S. laws that have restricted the importation of Iraqi cultural property into the U.S. since 1990. Specifically, the government cited 31 C.F.R. § 576.208 of the Iraq Stabilization and Insurgency Sanctions Regulations, which prohibits, in relevant part, “the trade in or transfer of ownership or possession of Iraqi cultural property or other items of archeological importance that were illegally removed, or for which a reasonable suspicion exists that they were illegally removed from locations in Iraq since August 6, 1990.” Violations of 31 C.F.R. § 576.208 can result in both civil and criminal sanctions. Although not directly cited in the complaint, the U.S. has also restricted the import of Iraqi cultural material under the Emergency Protection for Iraqi Cultural Antiquities Act of 2004, which obligates an importer of certain material to present evidence of proper possession or risk forfeiture under the Cultural Property Implementation Act, 19 U.S.C. § 2606.

Ultimately, Hobby Lobby settled the forfeiture action, relinquished a majority of the artifacts and payed a $3 million fine. The company also agreed to adopt internal policies and procedures that would govern future importation and purchase of cultural property. Green’s public defense of the company’s actions has been that the company was new to the world of acquiring artifacts and did not appreciate the complexities of the acquisition process. Given the wide-spread attention generated by this incident as well as the increasing public awareness of cultural property returns and restitutions generally, an importer of cultural material may not be able to plead ignorance in good faith for much longer. Even still, under the statutory provisions often used to seize and forfeit cultural property, an importer’s ignorance or good faith is not a relevant factor in deciding the property’s forfeitability. Thus, an importer of cultural material is more likely to avoid problems at the border and thereafter if they work to understand the legal and regulatory requirements for the trade in cultural property and heed all precautions on the frontend. Indeed, the take-away here is that American collectors and importers must work to ensure compliance with the laws and regulations that require truthful declarations at the U.S. border and transparency in the entry process.